What is a counterpoint?

In music theory, counterpoint is a technique in which two or more melodies are played independently but together form a harmonic structure. These melodies are arranged in such a way that they function both as independent melodies and in combination with the other voices to create an overall harmonic effect.

Principle of counterpoint

In contrapuntal composition, the main concern is the melodic autonomy of the individual parts of the composition, which can also be related to each other through imitative procedures. In counterpoint, the effect of the chord created by the superimposition of the different voices is in a sense accidental. Counterpoint emphasizes the melodic aspect rather than the harmonic effect.

In the Baroque period, many of the strict rules of the Renaissance were loosened and there was more rhythmic and harmonic freedom. This led to the popularity of counterpoint among composers of the time and the use of counterpoint with more complex harmonic structures (dissonances, tense intervals, etc.).

Composers such as J.S. Bach and Handel used counterpoint extensively in their works. It was also during this period that Johann Fux published his textbook "Gradus ad Parnassum", which is still considered the standard work on counterpoint.

Classification of counterpoints

Counterpoint can be classified in several ways, depending on the rules used and the relationship between the voices. Here are some of the more common types:

- Strict counterpoint: In this style, the relationships between the voices are highly regulated and the melodies often have simple rhythmic relationships. This style was especially common in the Renaissance and early Baroque periods.

- Free counterpoint: In contrast to strict counterpoint, the relationships between the voices are less strictly regulated. This allows for greater rhythmic and melodic complexity, as well as the use of chromaticism and dissonant harmonies. This type of counterpoint became very popular in the Baroque period, after the rules had been relaxed in the Renaissance.

- Imitative counterpoint: A style in which a melody is introduced by one or more voices and then imitated or repeated by the other voices, often at different pitches. A fugue is an example of a form that often uses imitative counterpoint.

- Inverted counterpoint: This is a technique in which melodies are reversed or "inverted" so that the upper voice is moved down and vice versa. Inverted counterpoint can be used in any of the above types of counterpoint and adds an extra layer of complexity and interest.

There are also special kinds of counterpoint in which two, three or more melodies are constructed simultaneously so that they fit together harmonically and are also interchangeable.

Counterpoints are also classified according to their rhythmic structure. These genres were first defined by Johann Joseph Flux in his textbook "Gradus ad Parnassum" and are still valid today:

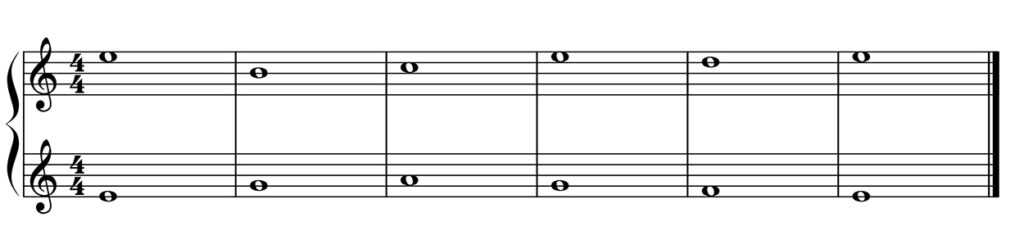

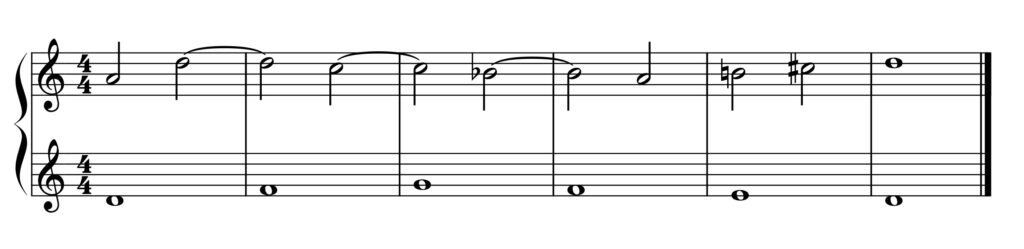

First specie (note against note):

Each voice has the same rhythm. Every note in one voice corresponds to exactly one note in every other voice. Normally, each voice begins and ends with a consonance (i.e., a sonorous, harmonious tonal relationship), while dissonances (discordant, tense tonal relationships) are avoided within the line.

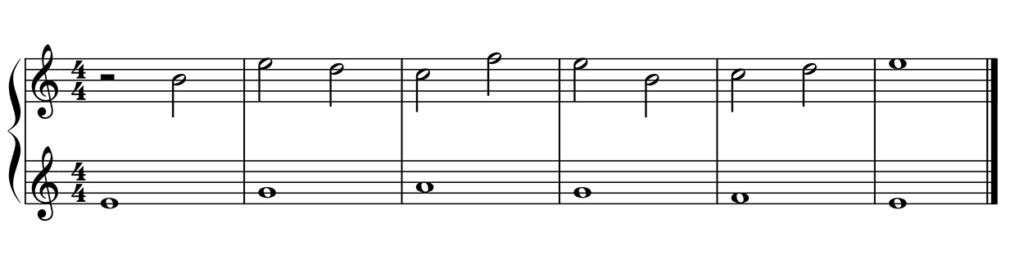

Second specie (two notes against one)

In this genre, one voice has two notes for each note of the other voice. Usually the first note of each pair is a consonance, while the second may be a dissonance.

Third specie (four notes against one)

Similar to the second genre, but now one voice has four notes for each note of the other voice. This allows greater rhythmic freedom and the use of more dissonances.

Notes offset against each other (syncopated or bound counterpoint)

In this genre, one or both voices are arranged in such a way that the note values are "shifted" and no longer correspond exactly to the bar beats. This can create dissonance on the beats (rather than between the beats), which creates a higher degree of tension.

Fifth specie (florid counterpoint)

This is the freest genre. It combines elements of all the previous genres, and the voices can move in different rhythms. This allows for a wide variety of textural and harmonic interests.

Conclusion

When you compose music, you may well be unconsciously setting counterpoints - a technique known colloquially among modern producers as "counter-melodies".

If not, I highly recommend it, because this is the secret of the best producers in the world. The ability to combine multiple melodies in a song into one big, beautiful "whole" takes a production to the next level.

Keep reading: