The key signatures determine the harmony of a song and are represented in the score by accidentals.

Knowing the key of a song is important for understanding what notes you can and cannot play when jamming with other musicians. Or for when you produce your songs and combine different melodic instruments. Because in every key there are notes that sound "right" and "wrong".

When you're producing music, it's important that you know a little bit about keys in order to play the melodies and chords on your instruments. For example, if you know you're producing a song in A minor, you know right away that the chords A minor, D minor, and E minor will sound good.

However, it is not always easy to tell what key it is - unless you can read the scores, in which case there are rules that you will learn here. But there are also methods for determining the key of a song by ear.

What is meant by key signature?

The key of a song determines which notes are on the minor or major scale. For example: in the key of C major, the notes of the scale are C, D, E, F, G, A, B; in the key of D major, they are D, E, F#, G, A, B, C#.

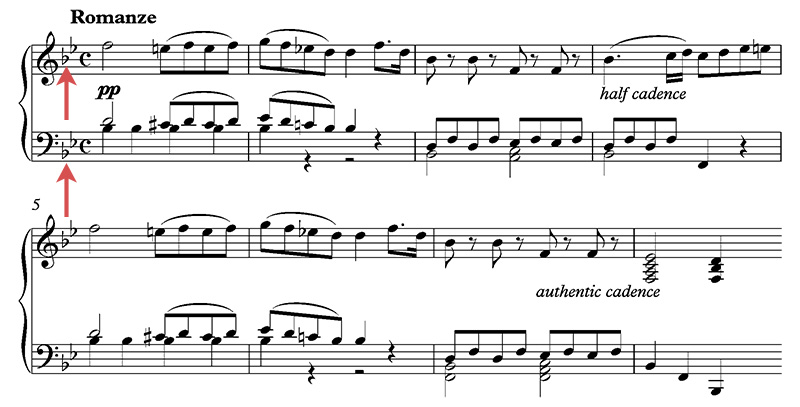

Keys are represented in scores by accidentals - these determine which notes are changed (played with # or b) to correspond to the key. As you can see, the C major scale has no notes changed by # or b, so the key has no accidentals.

D major, on the other hand, has changed the F to an F# and the C to a C# - so this key has 2 accidentals, the F# and the C#.

The key also helps you to know which chords fit into the piece and what mood they create. There are rules in harmonies about chord intervals - for example, the chord progression 1,4,5 is very popular in minor scales because it always sounds nice.

The intervals between notes or chords are called intervals. 1 is the keynote, 4 is the fourth (the 4th note of the scale) and 5 the fifth (the 5th note of the scale). In C major, C is 1, F is 4 and G is 5..

Identifying the key signature of a piece of music

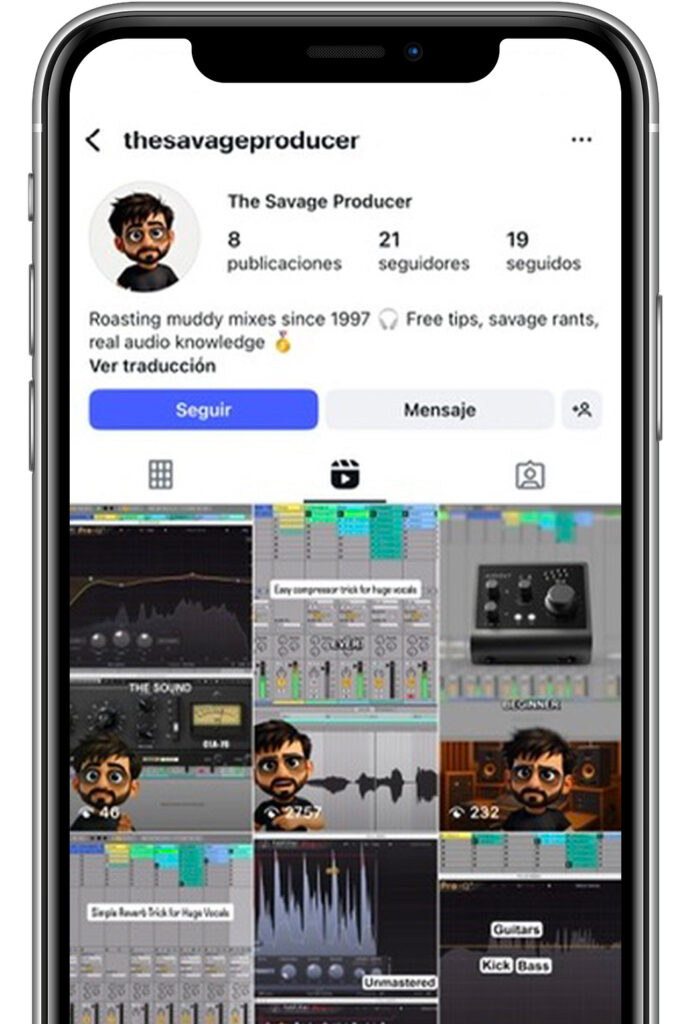

If you have the score of the song in front of you, you need to look at the very beginning to see what the key signature is. It can be either # or b, but not both. Usually there can be up to 7 accidentals.

With this simple rule you can determine the key by the number of # or b:

- If there are no accidentals, we are on C major.

- For keys with crosses, take the very last cross and go up a semitone from that note. Then you have the root of the major key.

- In keys with bs, the penultimate b is the root of the major key. If there is only one b, you are in F major.

For every major scale there is a parallel minor scale. So it can be one or the other. Determining this exactly is sometimes very complicated and only possible for real experts in music theory.

As a rule of thumb, however, 99% of all songs start with the root note. So look for the first note - it will be either the root of the major or minor scale.

You can often tell by listening whether they are major or minor chords, since major chords sound happy and minor chords sound rather sad. If you're not sure, just play both chords on your MIDI keyboard or guitar. Then you can hear which chord sounds better and fits the key better.

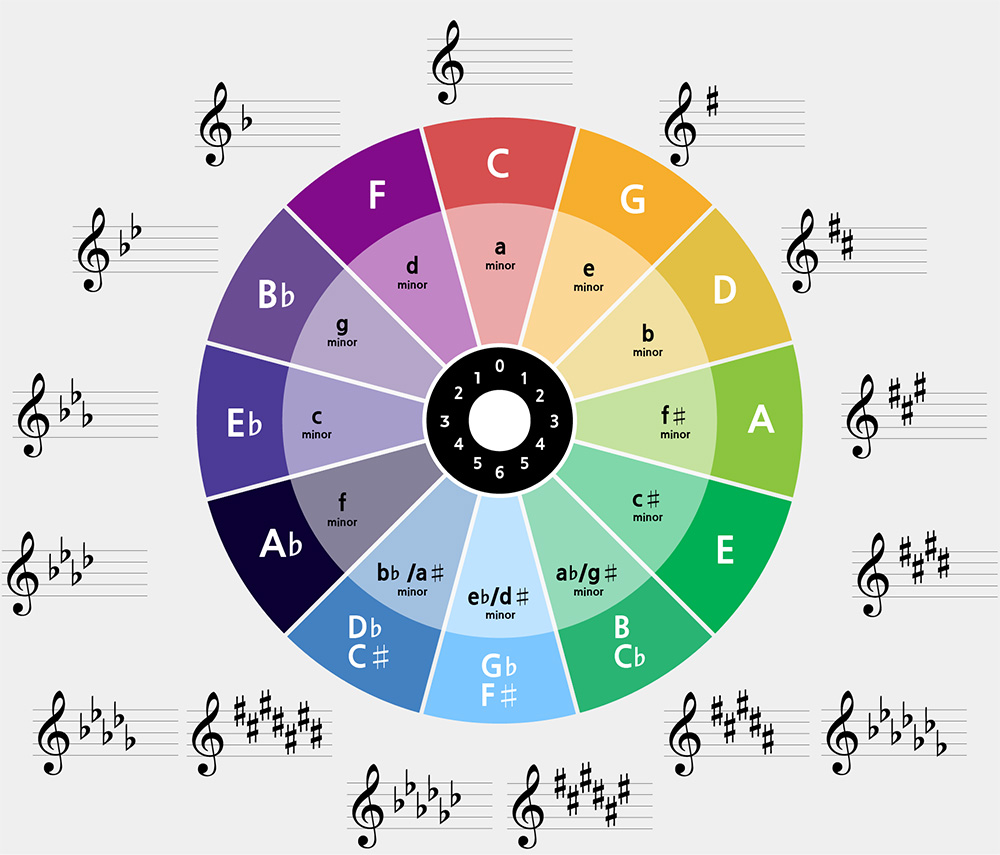

Arrangement of the keys in the circle of fifths

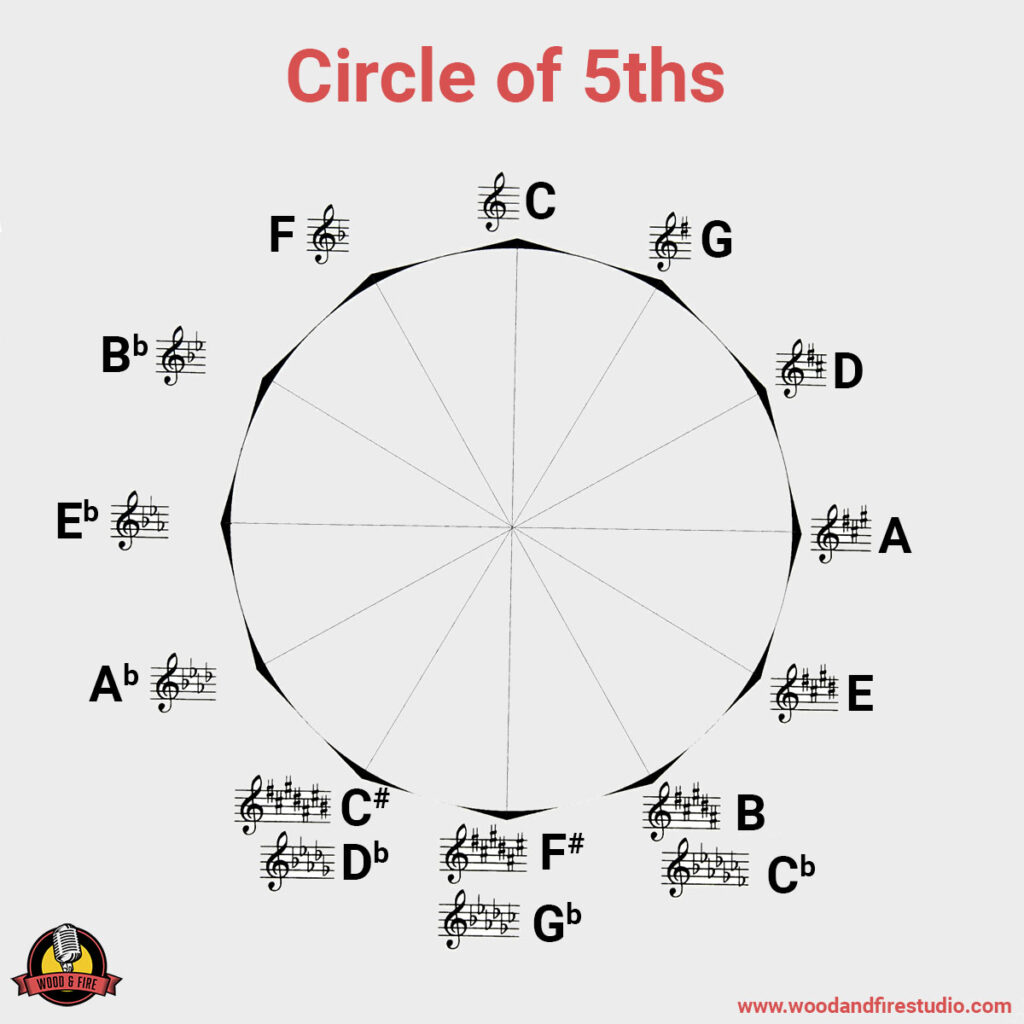

The keys are arranged in a circle in the well-known circle of fifths. There you can match the number of accidentals with the corresponding major keys. The parallel minor key can be found by going 3 semitones down from the root of the major key (C major/a minor; D major/b minor; E major/c# minor; etc.).

Keys without accidentals

Without accidentals there is only the key C major and the parallel key A minor.

Keys with cross accidentals

- 1 cross: F#→ G major or E minor

- 2 crosses: F#, C#→ D major or B minor

- 3 crosses: F#, C#, G#→ A major or F sharp minor

- 4 crosses: F#, C#, G#, D#→ E major or C sharp minor

- 5 crosses: F#, C#, G#, D#, A#→ B major or G sharp minor

- 6 crosses: F#, C#, G#, D#, A#, E#→ F sharp major or D flat minor

- 7 crosses: F#, C#, G#, D#, A#, E#, H#→ C sharp major or A sharp minor

Keys with b-sign

- 1 b: Bb→ F major or D minor

- 2 b: Bb, Eb→ B flat major or G minor

- 3 b: Bb, Eb, Ab→ E flat major or C minor

- 4 b: Bb, Eb, Ab, Db→ A flat major or F minor

- 5 b: Bb, Eb, Ab, Db, Gb→ D flat major or B flat minor

- 6 b: Bb, Eb, Ab, Db, Gb, Cb→ G flat major or E flat minor

- 7 b: Bb, Eb, Ab, Db, Gb, Cb, Fb→. C flat major or A-flat minor

This may seem overwhelming at first, but over time you will learn it by heart without even trying. However, you can memorize the following so that you always know how many accidentals go with each key signature:

- We know that C major and A minor have no accidentals.

- To find out the number of crosses of a major key, always go up a fifth (to the right of the circle of fifths) and then always add a cross. The same applies to the minor keys, by going up a fifth from the A.

- To find out the number of bs in a major key, you go up a fourth from C (one step to the left on the circle of fifths), which is equivalent to going down a fifth. With each step, a new b is added. The same applies again for minor keys.

What are enharmonic keys?

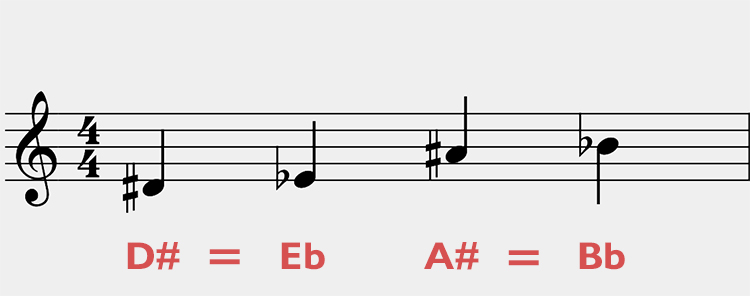

There are some keys that are theoretically missing from this list. For example, where is D-sharp major or A-sharp major?

These keys are represented by their enharmonic keys E-flat major and B-flat major. In practice, they are the same notes, so it is not necessary to perform them twice in the circle of fifths.

In music notation, the same note can be represented in different forms. I can write a D-flat also as C-sharp , or a F as E-sharp - these are the enharmonic equivalents.

Which one to choose is a question of harmony theory. It is usually clear, though, because:

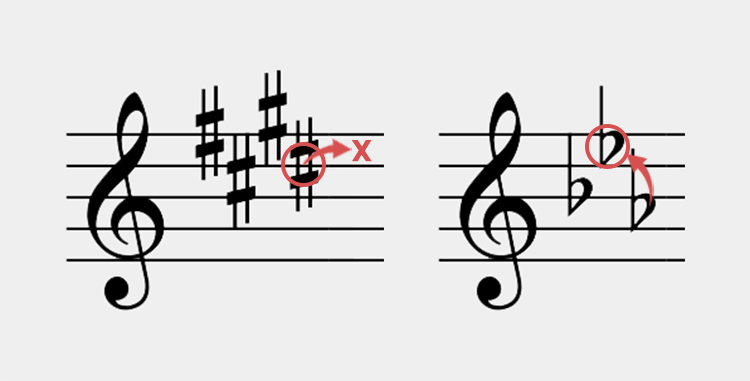

- To determine the number of crosses of D sharp major, the above semitone rule is applied.

- That means I would have to have two crosses on the C to then get to D sharp with the semitone up.

- That is possible, of course, but that would be a total of 9 accidentals at the beginning of the score - for simplicity's sake, it is better to write E-flat major, where only 3 bs are needed.

So when you start with double sharps and double bs, you know you're better off going in the other direction of the circle of fifths.

The importance of keys for one's own productions

If you are already producing and composing music, you are consciously or unconsciously using key signatures and intervals. Ultimately, composing is about using the different intervals within a key to create different chord progressions.

In theory, you are free, but there are intervals that sound good or bad, intervals that sound happy or sad, hopeful or depressing, and so on. And there are recurring patterns - certain chord intervals that go down particularly well with the listener and are therefore used in many songs.

When you start composing and run out of ideas, you can experiment with the following chord progressions (intervals). Each number represents a note or chord of a scale. For example, in F major F the I, B the IV and C the V.

I-IV-V: The Pop Classic (works in major and minor)

I-V-vi-IV: Full of emotion and feelings (lower case is minor)

I-IV-V-IV: Another pop classic

You can find more popular chord progressions in my article about musical cadences.

Conclusion

Even though music theory is not a prerequisite for good music making, it is always helpful to deal with basic terms and concepts. Key signatures and scales are especially useful when making music with other musicians - they facilitate communication and enable improvisation.