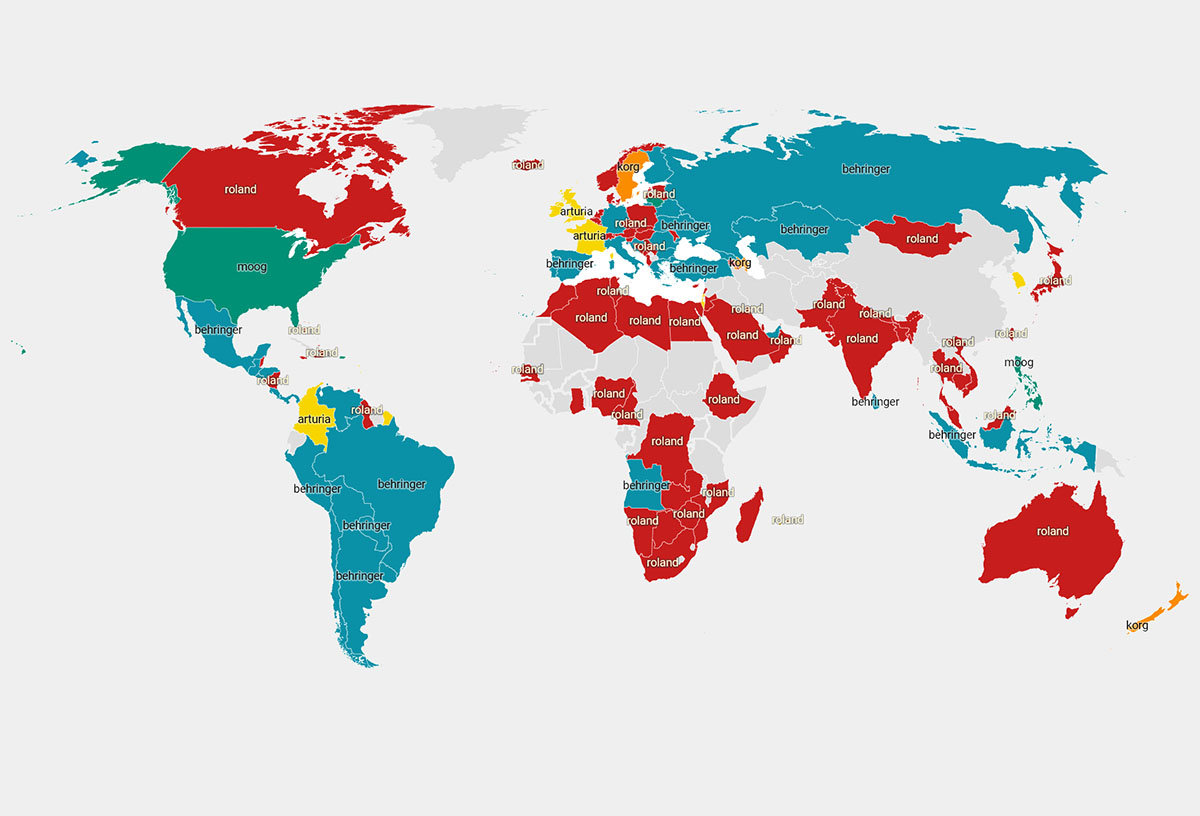

Learning to read music opens up a musical world that would otherwise remain hidden. Imagine a map of the world without labels - it looks beautiful, but without the names of countries, cities, and oceans, it's just a colorful mess. Sheet music is your map of the world of music. It tells you where you are in a piece of music, which direction to go, and how to get there.

Music notation is also a universal language that allows musicians to communicate their ideas and feelings with precision, no matter what culture or language they come from. Whether you're interpreting a classical score by Mozart or the latest pop hit by Adele, sheet music is the bridge between the composer's creative expression and your own musical interpretation.

The ability to read music also allows you to develop your skills on your own. You can explore old pieces without relying on someone else to play or explain them to you. You can delve deeper into music, analyze compositions, and expand your understanding of melodies, harmonies, and rhythms.

Learning to read sheet music - Step 1: Basics

To read a score, you first need to understand the most important musical signs and symbols. You can think of them as a language, where each character is a different letter that, when combined with other characters, forms words and sentences.

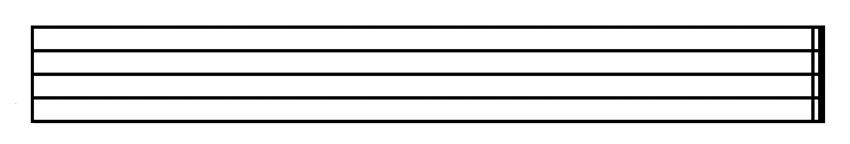

The staff

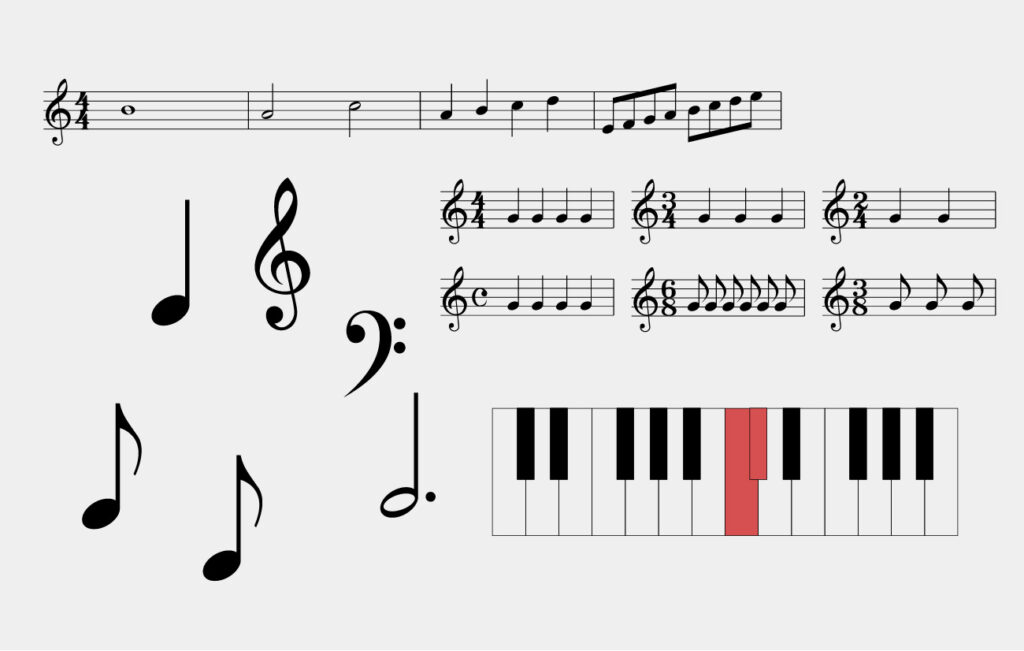

A staff is like a blank sheet of paper in music: it is the template on which the different notes are placed. A staff consists of 5 lines and 4 spaces, each of which is assigned to a note.

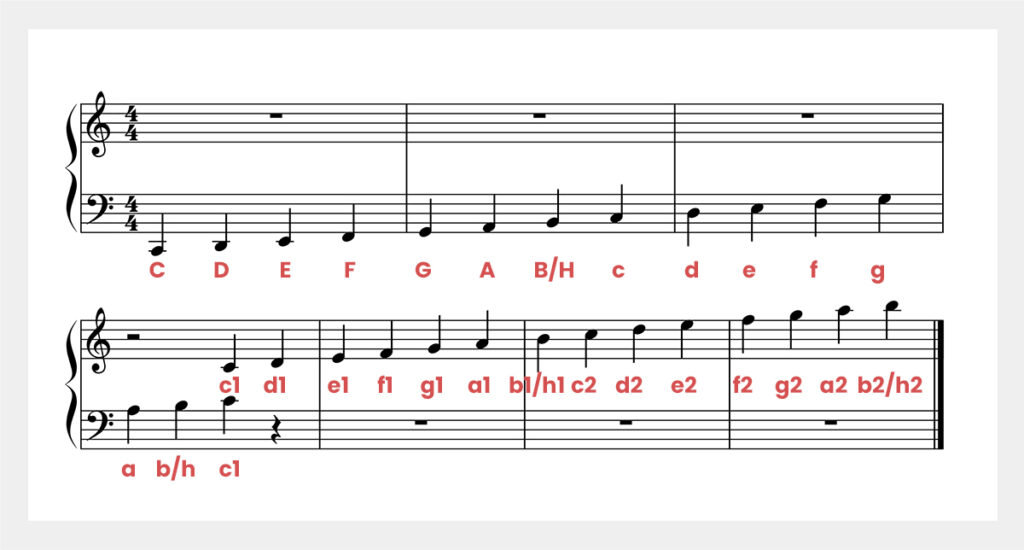

There are 7 notes in total, which in English are called from A to G (A, B, C, D, E, F, G). In German, an "H" is used instead of the "B" (A, H, C, D, E, F, G), and in Latin languages such as Spanish or Italian they are called La, Si, Do, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol. Which note is on which line or in which space is determined by the clef.

Clef

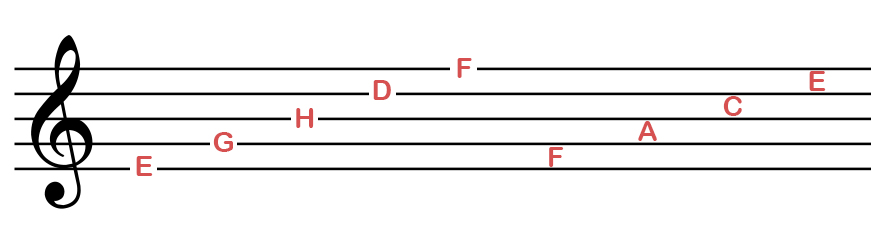

A clef determines where which note is located on the staff. There are many different clefs, but the two most important are the treble clef and the bass clef.

Treble clef

The treble clef is used for high instruments and indicates the position of the note G on the staff - hence it is sometimes called the G clef. The treble clef forms a circle around the musical note G (so you can quickly find all the other notes if you forget them).

To remember the names of the notes on the lines, you can use the mnemonic "Every Good Bird Does Fly"; for the notes in the spaces, the word "FACE".

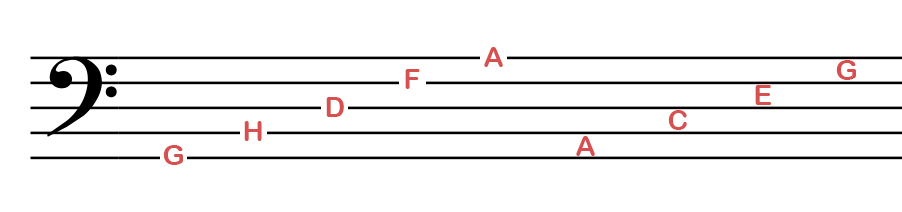

Bass clef

The bass clef is also often used for low instruments, as the name "bass" implies. The dot in the illustration marks the note F, which is why it is often called the F clef. It marks notes in low register that are difficult to represent with the treble clef.

When you read music for double bass, cello, electric bass, tuba, or baritone saxophone, it is written in bass clef.

To get a better idea of why we need different clefs, it is helpful to look at the whole range of music notes. It quickly becomes clear that it would be difficult to represent the low notes in treble clef - you would need a lot of auxiliary lines under the staves.

However, there are some instruments, such as some balalaikas, that sound an octave lower than the notes describe. But these tend to be exceptions.

Note value

➔ Click here for the detailed article on musical note values

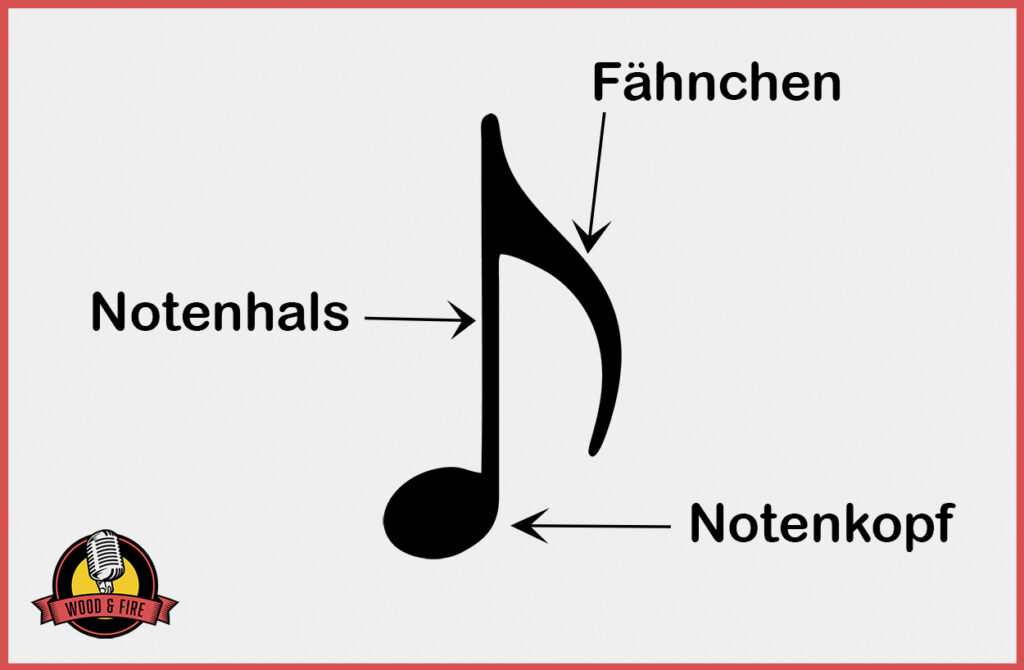

Musical notes are placed on a staff and give us two important bits of information: What note is being played on the instrument, and how long it is being played. A musical note is made up of three parts that indicate the value of the note:

Note head: A circle that can be filled or empty. It lies either on a line or on an empty space on the staff and thus determines which note is played. Depending on whether the circle is empty or filled, the note will have a different length.

Stem: A line that starts at the note head and points either up or down. Not all notes have a stem - for example, whole notes have no stem. It does not matter whether it points up or down - you simply choose the notation that makes the score easier to read in the overall context.

Flag: Flags are not in every note, but only in eighth notes or shorter. Their only purpose is to indicate note length.

The length of musical notes

Now that we know how the pitch of a note is determined, we only need to know the other half: the note length. This is determined by the combination of different note heads with different flags.

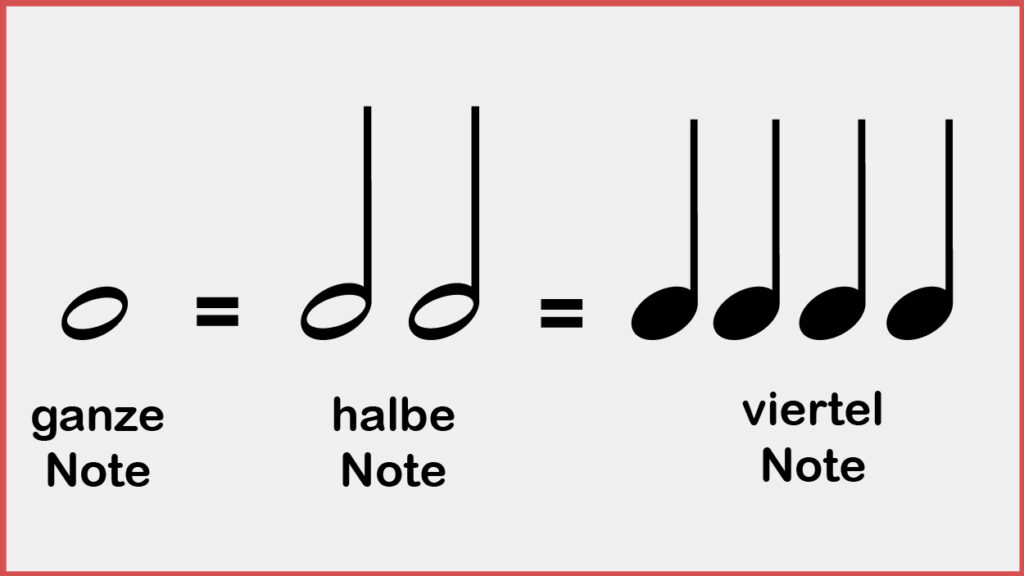

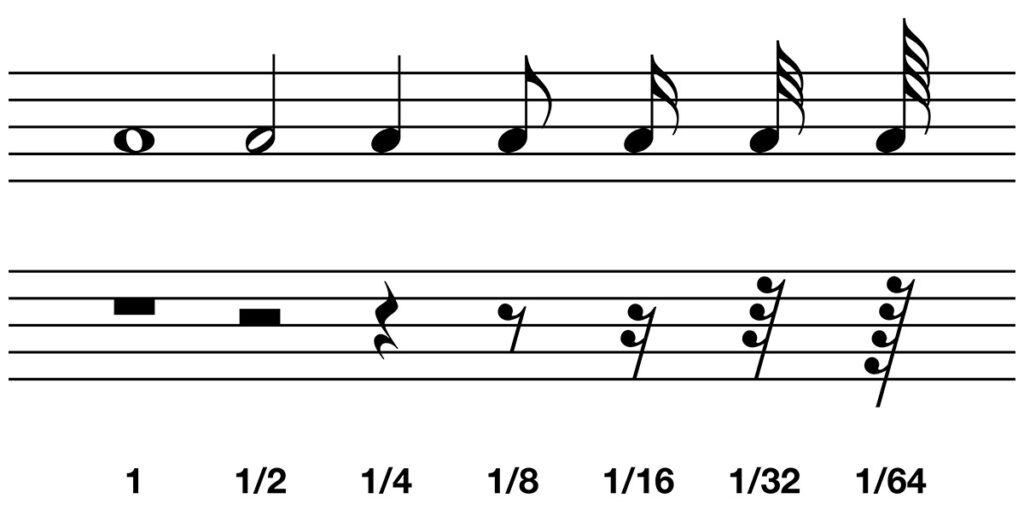

A whole note is 4 beats long, i.e. it lasts a whole 4/4 bar. It is the longest note that exists and is represented by an empty note head with no flags. If you halve the length of the note, you get a half note; if you halve it, you get a quarter note.

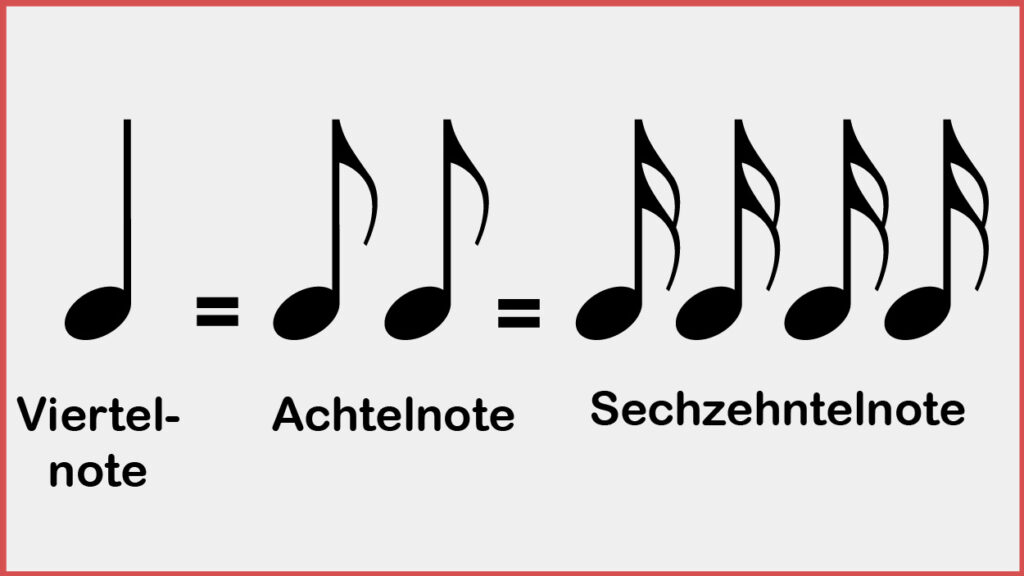

And you can divide them further to get eighths, sixteenths, thirty-seconds, etc., simply by adding more flags to the note.

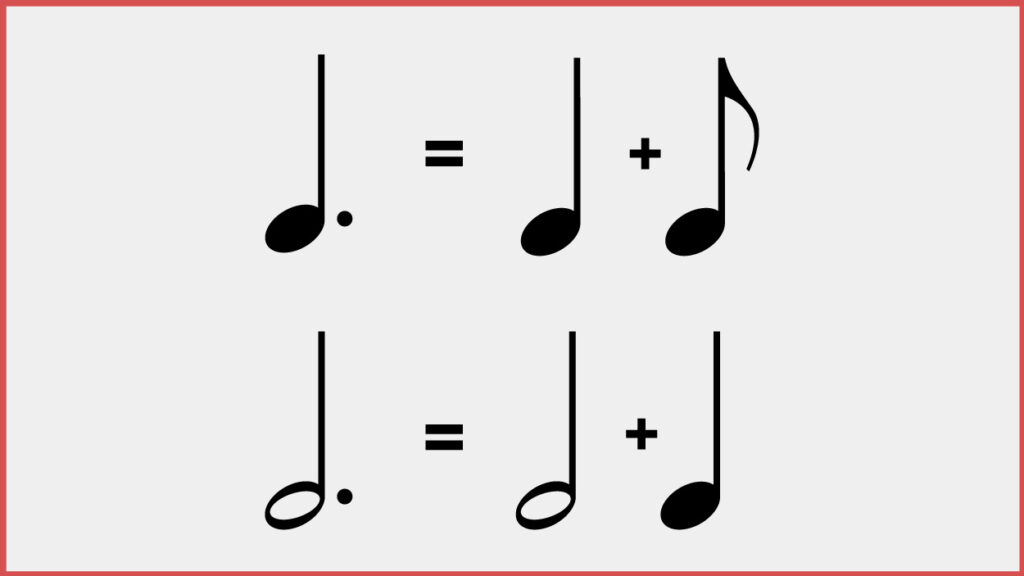

To represent note lengths that are not divisible by 2, dotted notes must be used. A dot after the note makes the note 1.5 times as long, i.e. a quarter note is supplemented by an eighth note, a half note by a quarter note, and so on.

Notes can also be extended by connecting two notes with a tie. This is used whenever the note extends beyond the bar. The length of the newly created note is equal to the length of the two notes joined together.

It is also possible to divide a rhythmic unit into three instead of two - this is called a triplet. A quarter note triplet lasts as long as two normal quarter notes.

Rest

Just like notes, there are rests - they indicate how long an instrument will not be played. Rests must always be notated, you can't just leave a bar empty because no notes are being played.

Rests have the same length as notes and can also be dotted. Here is an overview of which rest length corresponds to which note:

Step 2: Understanding the rhythm

➔ Click here for the detailed article on the rhythm of music

Okay, now that we know how to interpret each note in a score, we need to think about rhythm. There are two main factors that affect the rhythm of a song: time signature and tempo.

Time signature

A time signature in music is a kind of rule that helps you understand how the beats in a piece of music are counted. The time signature is usually at the beginning of a score, right after the clef and the key signature. It consists of two numbers, one above the other.

The top number is the number of beats per bar. A bar is like a small time frame in music, and each bar usually has the same number of beats. So if the top number is a 4, each bar has 4 beats. This is why you may have heard music counted as "1, 2, 3, 4; 1, 2, 3, 4...".

The lower number indicates which note counts as a beat. If the lower number is a 4, this means that a quarter note counts as a beat. If the lower number is an 8, an eighth note counts as a beat, and so on.

For example, in a 4/4 time signature, which is very common and is sometimes called "common time" (which is why you can write it with a capital C), each bar has four beats, and each quarter note counts as one beat. This means that you can have 4 quarter notes, 8 eighth notes, 16 sixteenth notes, or any other combination that gives the same total in each bar.

Another common time signature is 3/4 time, where a bar has three beats and a quarter note is one beat long. Many waltzes are in 3/4 time, so you can count them as "1, 2, 3; 1, 2, 3...".

Time signature provides a framework for understanding the rhythm of music. It helps musicians read the music and keep a steady beat, and it gives the music a certain feel or groove.

Tempo

➔ Click here for the detailed article about the tempo

When you tap your foot or nod your head during a song, you are following the rhythm of the music. Some songs have a fast tempo and make you want to move and dance quickly, such as many dance songs or fast pop songs. Other songs have a slow tempo that makes you sway slowly or feel relaxed, such as ballads or lullabies.

In sheet music, tempo is usually indicated at the beginning of a piece with a term that gives an idea of speed, often an Italian word. Terms like "Allegro" mean that the music should be played fast and lively, while "Adagio" means that it should be played slowly and quietly.

However, if you want to specify the exact tempo, you must use metronome markings such as "♩= 120", which means to play 120 beats per minute (each beat is a quarter note).

The tempo can also change during a piece of music, with some parts getting faster and others slower. Good composers use tempo changes to evoke certain feelings in the listener.

Bar lines

The individual bars are separated by a bar line, which is nothing more than a line standing vertically on the pentagram and going through all the lines. At the end of the last bar of a song, a final line is used instead of a bar line (two bar lines in a row, the second thicker than the first).

Step 3: Musical notes and rhythms become melodies

Now that we know how to interpret individual notes and how to maintain a rhythm, nothing stands in the way of composing melodies, except the keys. Keys are groups of notes that, when played together or in a certain context, sound good and are perceived as "beautiful.

In music, the key of a song is a kind of foundation around which the notes of the song revolve. It is like a guideline that tells us which notes sound good in the piece and which do not. Note: I say guideline, not rule, because it doesn't forbid notes - it's just a guide.

When we speak of the key of a song, we mean two things in particular: the root note (tonic), the first and most important note on which the song often begins and ends, and the scale, a series of notes used primarily in the song.

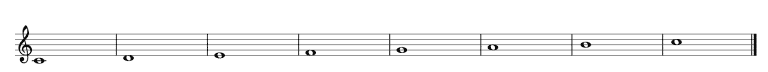

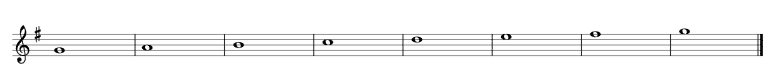

Let's take the simplest of all scales, C major, as an example. The root of this key is C, and the notes would be all the white keys on a piano:

As you can see, only white keys are played in C major, but not all intervals (distances between adjacent notes of the scale) are equal - between E and F and between B and C there is only a semitone difference, while all other intervals are whole notes. So we notice: the semitone differences are between the 3rd and the 4th note and between the 7th and the 8th note.

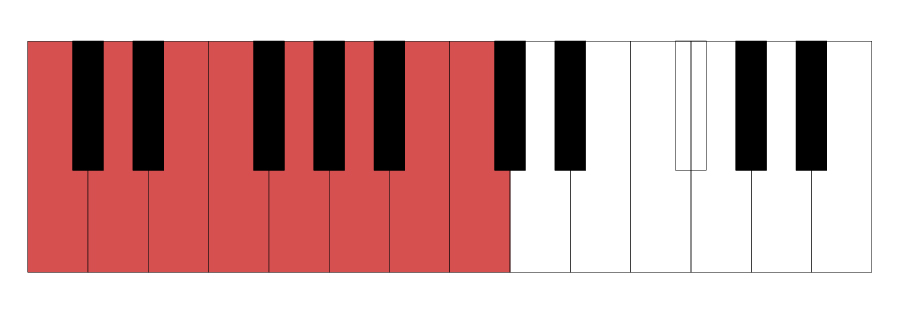

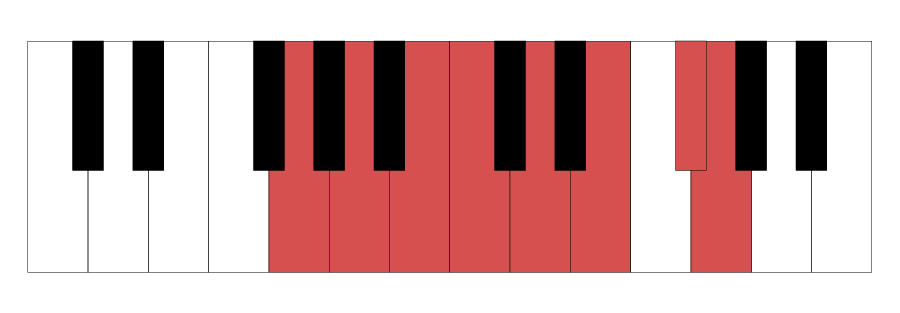

In any other major scale, the semitone intervals are in exactly the same place, but the 3rd note in G major is different from the 3rd note in C major, so it gets a little more complicated. The key of G major looks like this:

There is an accidental, a cross, on the F. This turns the F into an F sharp (a semitone higher) and ensures that the semitone differences are in exactly the same place as in C major, between the 3rd and the 4th and between the 7th and the 8th.

So these are the notes that definitely sound good in this key and can be used to build melodies. If you want to know more about this, you can find a detailed article about keys and accidentals here.

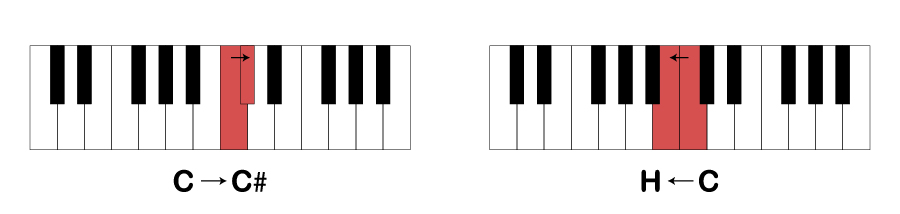

As you have already seen, a cross (♯) in front of a musical note makes that note a semitone higher. b's (♭) do exactly the opposite, they make the note a semitone lower. A semitone up on the piano means a step to the right to the next key, whether white or black. A semitone down means the same thing, but to the left on the piano.

In the score, crosses or b's can be placed directly before the note, in which case the accidental is valid for the whole bar (if a ♯ is placed before a C, then every C in the bar becomes a C sharp). The accidentals can also be placed at the beginning of the score, immediately after the clef, in which case they apply to the entire score.

However, if you want to cancel the effect of the accidental in either of these cases, use a natural (♮). This cancels the effect of all previous accidentals for the entire bar.

Step 4: Chords

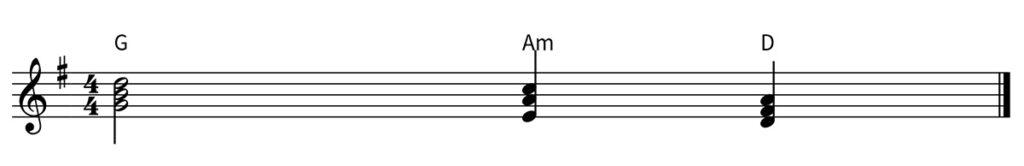

Chords are groups of at least three different notes played together and tuned to harmonize. Depending on whether they are made up of minor or major notes, they create their own mood.

In music, chords provide harmony and can evoke feelings in the listener. By cleverly stringing chords together, cadences (chord progressions) are created that give structure and meaning to a song.

In a score, you simply write the notes on top of each other and connect the stems (if any). You can also write the name of the chord directly above the notes to make them easier to read.

Step 5: Dynamics

Dynamic symbols are not so important at first, because you are busy with everything else. But as soon as you start playing notes on an instrument, you have to deal with them.

The dynamic indicates how loud or soft a passage in a piece should be played. You can emphasise individual musical notes dynamically by writing a marcato sign (>) over the note. This means that this note should be played louder than all the others.

When a longer passage is to be dynamically changed, it is common to write the terms for volume in Italian, e.g. forte (loud) or piano (soft). The following table lists all terms and their abbreviations that appear in scores.

| Name | Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Pianississimo | As quiet as possible | |

| Pianissimo | Much quieter | |

| Piano | Quiet | |

| Mezzopiano | Moderately quiet | |

| Mezzoforte | Moderately loud | |

| Forte | Loud | |

| Fortissimo | Much louder | |

| Fortississimo | As loud as possible |

Dynamic differences make a piece of music much more interesting and varied, and can also do a lot to evoke certain emotions. A suddenly loud passage can startle the listener, while a passage that starts softly and then gets louder builds suspense.

Free tools: How to learn at home

To practice, it is very helpful to start with sheet music from songs you know well, such as sheet music from a popular movie like "Indiana Jones" or "Star Wars". Or from popular pop songs. Whatever you like, and especially whatever you know well.

On musescore.com you can find a lot of free sheet music, but for the really cool and well-known songs you usually have to pay. On musicnotes.com you can find sheet music for almost every song.

If you want to write your own notes, I recommend Noteflight - it's 100% free in the basic version, which is quite sufficient for beginners. I use it myself and wrote most of the notes for the images in this article with it.

Conclusion

Once you have followed all of these steps, you will have the knowledge necessary to at least begin to understand a score. Fluency in reading and playing music comes with time and practice - for professional orchestral musicians, reading a score is like reading a book because they have so much experience.