What is a cadence in music?

In modern harmony theory of music, cadence (Italian cadenza, from Latin cadere, "to fall, end") refers to a sequence of certain chords that are considered the basic building blocks of harmony and usually mark the conclusion of a passage or an entire piece. A cadence is thus a sequence of popular chords.

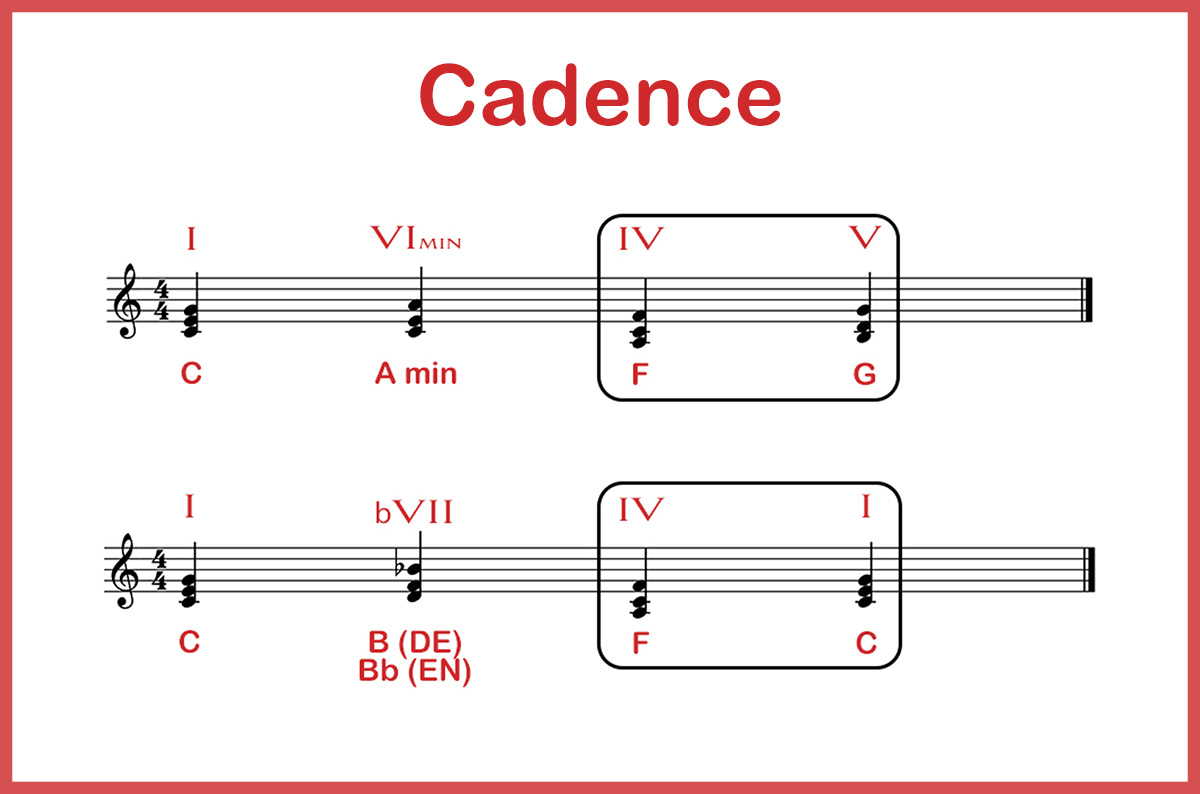

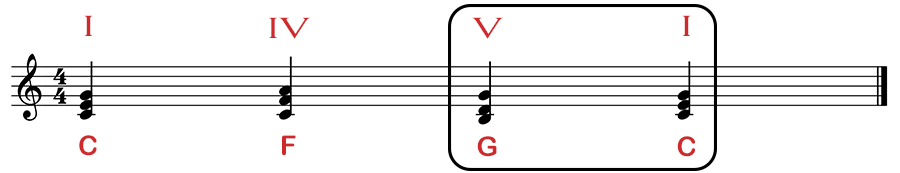

For example, the cadence I-IV-V-I (tonic, subdominant, dominant, tonic) is a basic chord progression in pop music that can be used to play many pieces of music. When composing, if you don't know what chords to play next, such popular cadences can be very good inspiration.

Tip: The circle of fifths is very helpful when creating your own cadences.

What do you need cadences for?

A musical cadence serves as a guide or point of reference when improvising with other musicians or composing a piece yourself.

So if you agree on a key for a jam session, say D major, and you set a cadence, say I-IV-V-I, then every musician knows what to play. He knows that D major is followed by G major and then A major. That way, everybody can improvise, but they only play the notes that go with the chord, so the harmonic coherence is maintained.

And if you find yourself lacking inspiration for chord progressions when composing, you can simply search for well-known cadences from other songs and try them out and adopt them (melodies are copyrighted, chord progressions are not).

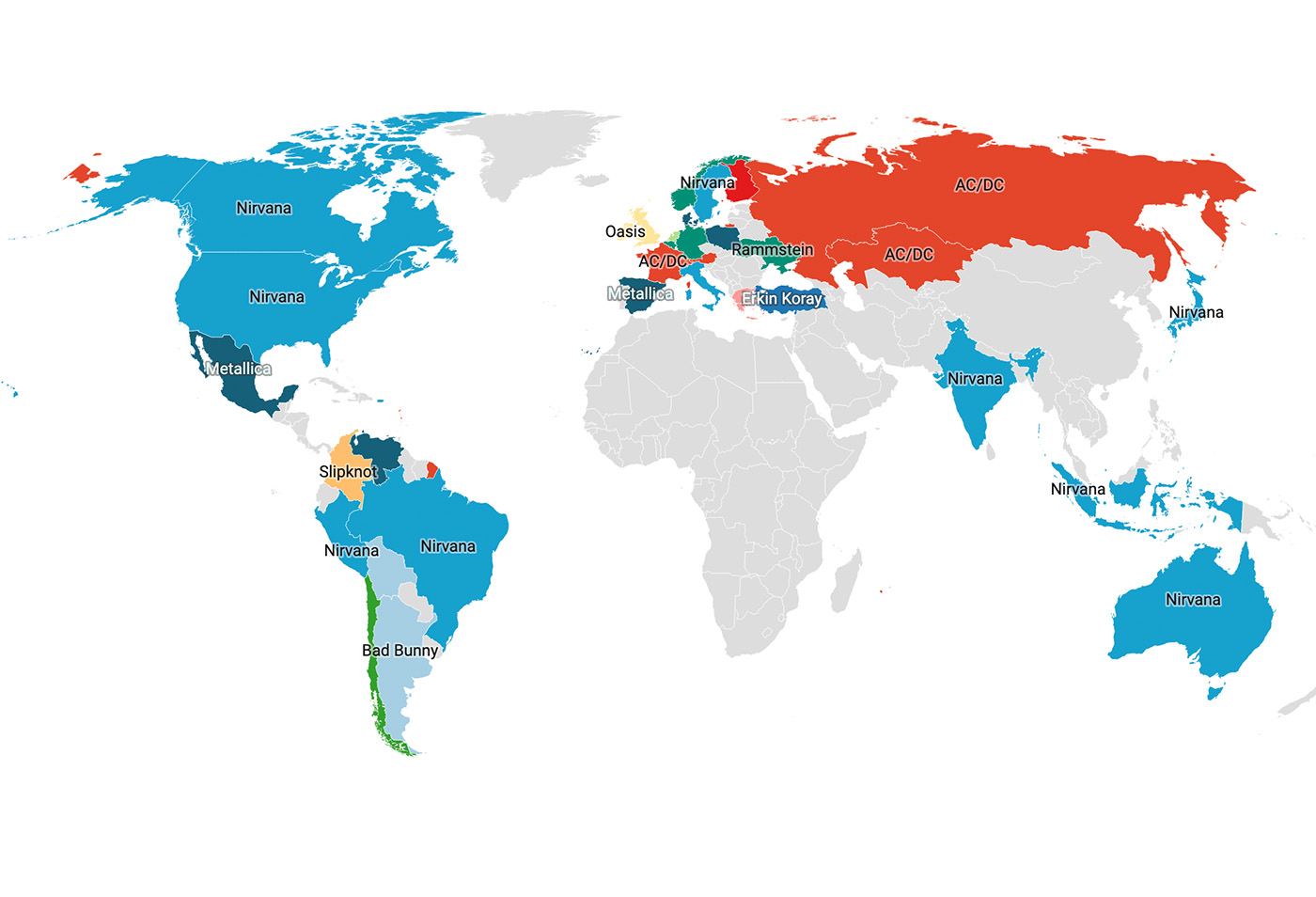

Here is a list of 10 popular cadences that have been used in the composition of countless hits throughout music history, explained in the keys of C major and A minor, depending on whether the first degree is minor or major.

| Chord progression | Genre |

|---|---|

| I-IV-V (C-G7-F) | Blues, Rock 'n' Roll, Country, Folk, Pop |

| I-V-vi-IV (C-G-Am-F) | Pop, Rock, Ballads, Indie |

| ii-V-I (Dm7-G7-Cmaj7) | Jazz, Bossa Nova, Fusion, Bebop |

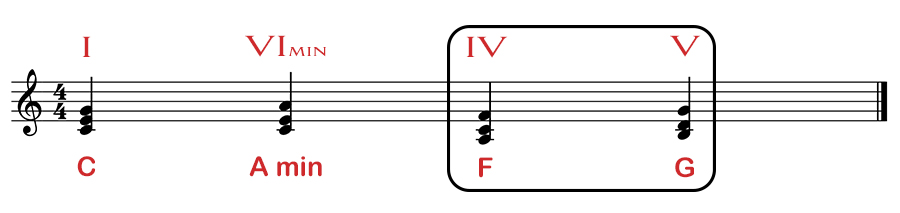

| I-vi-IV-V (C-Am-F-G) | Doo-wop, Pop, Rock, Rhythm & Blues |

| vi-IV-I-V (Am-F-C-G) | Pop, Rock, Alternative, Ballads |

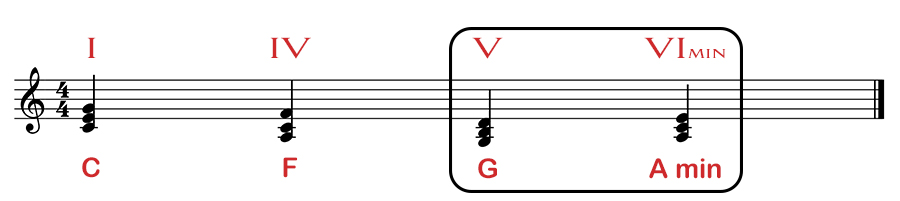

| I-IV-vi-V (C-F-Am-G) | Pop, Rock, Ballads, Indie |

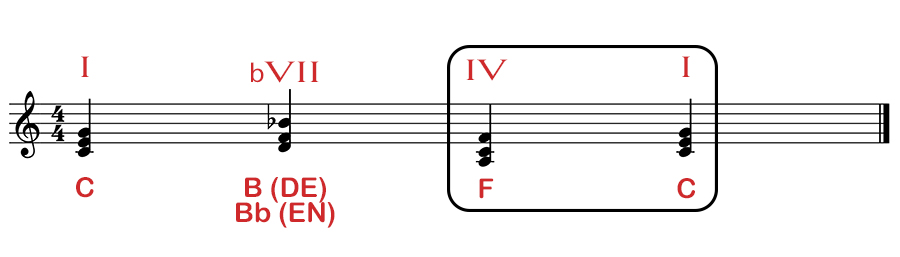

| I-bVII-IV-I (C-Bb-F-C) | Rock, Pop, Alternative, Psychedelic |

| i-bVII-III-IV (Am-G-C-D) | Rock, Pop, Alternative, Indie |

| I-V-ii-IV (C-G-Dm-F) | Pop, Rock, Ballads, Folk |

| i-IV-i-V (Am-Dm-Am-E) | Flamenco, Bolero, Latin Pop, Tango |

The musical styles listed are examples of where these chord progressions are most common.

Keep reading: Sheet music reading made easy

Musical cadence as a structured formula for the closing statement

When the root chord in a song changes to another chord, a harmonic tension is created. Our ears expect this tension to be resolved - otherwise there is a feeling of incompleteness (which is sometimes desirable).

And this is where the cadences come in, because they help to find a suitable ending, which has a different effect on the listener depending on the ending chords.

Types of cadences according to classical harmony theory

Essentially, there are four different types of cadences in classical harmony theory, which are classified according to the way they end and have a different effect on the listener or arouse certain emotions:

Authentic or perfect cadence (V → I)

An authentic cadence consists of a dominant chord (V or V7) followed by a tonic chord (I). In a perfect authentic cadence, the tonic in the bass is in both the dominant and tonic chords, and the highest voice also has the tonic in the final tonic chord. This cadence has a very strong resolution and impressively confirms and concludes the key.

Plagal cadence (IV → I)

The plagal cadence, also known as the "church ending" or "amen cadence," consists of a subdominant chord (IV) following a tonic chord (I). The resolution of this cadence is less than that of the authentic cadence, and it is often used in church music and hymns.

Half-final or half-cadence (I, II, IV or VI → V)

Here the cadence ends on the dominant chord (V), creating a sense of tension and incompletion. This type of cadence is often used in the middle of musical phrases to introduce a pause or transition.

Deceptive cadence (V → VI)

A deceptive cadence leads from the dominant (V) to a chord other than the tonic (I), usually to the parallel (VI), or to another chord that contradicts the listener's expectations. This creates a surprising twist that adds tension or drama to the piece and creates a sense of incompleteness.

Cadence and the different forms - an ambiguous term

Originally, only certain chord progressions consisting of four chords, where the last chord is the same as the first, and which form the conclusion of a piece, were called cadences. However, the term has expanded to include any chord progression that is particularly clichéd or common.

Cadences usually consist of four chords, but there is no limit to the number of chords - nowadays, even chord progressions with 10 chords are called cadences. In modern music, however, such long chord progressions are not so common, and most modern popular songs still consist of 4 chords.

Building a cadence

If you want to create your own cadences for your compositions, you need to understand how the structure works. To do this, we will look at the two basic keys, C major and A minor, and their corresponding notes to understand the structure of cadences in both major and minor keys.

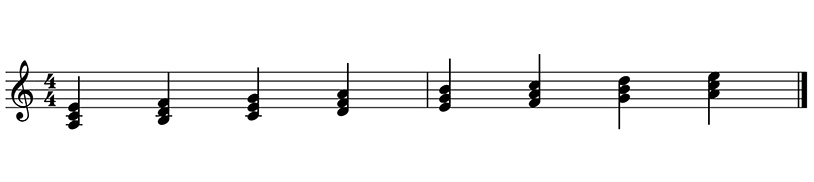

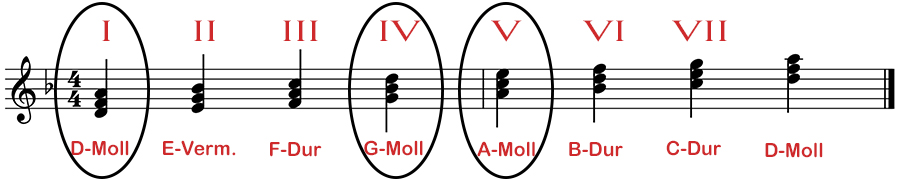

Now we construct the natural chord from the key for each tone - these are the chords that result if you simply go up two steps twice in the pentagram without adding any more accidentals - and we get the following constellation:

This is our model for building different cadences from these chords - depending on whether the base chord is minor or major, you choose the appropriate variation. For example, if the base chord is D major, you need to find all the notes of the scale again and build the corresponding natural chords for that key (in this case there are 2 crosses as accidentals). Our article about the different keys and their accidentals can help you with this.

Example: Building major cadences

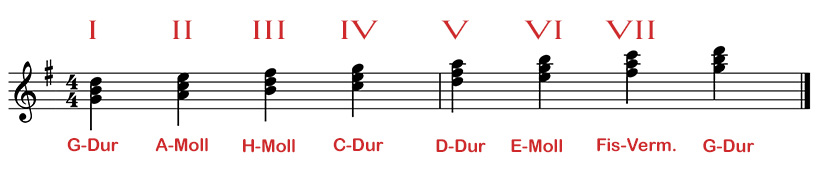

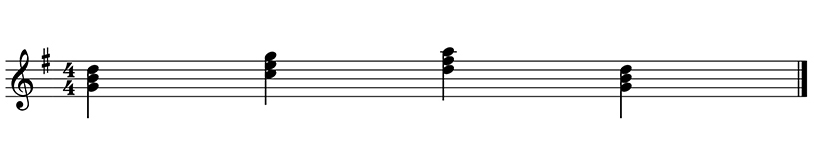

As an example: We want to find the chord progression/cadence I-IV-V for G major. To do this, we again write down all the chords that naturally occur on the G major scale:

Then we just take the first, the 4th and the 5th degree and we have our chord progression: G major, C major and D major.

Example: Building cadences in the minor key

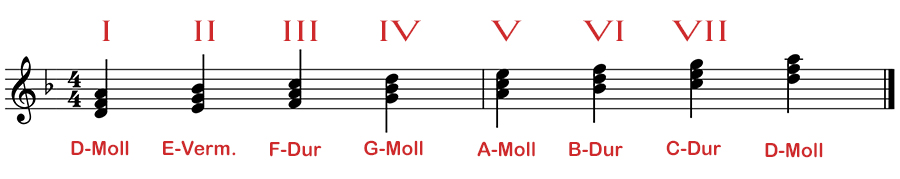

Now we do the same with a minor key to understand the process here as well. As an example, let's take D minor and again look for the cadence I-IV-V (sometimes you also use lowercase letters for the steps when it comes to minor chords, so in this case you would write i-iv-v).

To do this, we first write down all the notes of the scale and create the corresponding natural chords.

And already we can choose our cadence, in this case D minor, G minor and A minor.

If you construct chords so that each note of the chord simply moves up one step, as in the examples above, you get what are called parallel directions of motion. These are created when each voice (i.e., each chord note) moves the same distance in the same direction in the transition from one chord to the next. This should be avoided as much as possible in compositions to keep the harmony exciting - and good voicing helps.

What is the voicing?

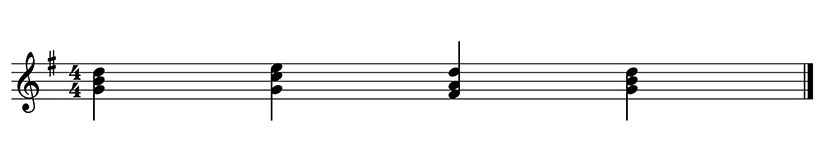

Voicing describes how each voice of a chord changes to the next chord. Each chord consists of at least 3 notes, and when changing chords, each voice can go in a different direction, either up or down, and still play the correct chord.

Good composers vary the voice leading for chord changes, i.e. the root of the chord is not always the lowest note, but sometimes the third or the fifth is the lowest note. This makes the composition much more interesting and exciting than if the same voice leading is always used for every chord.

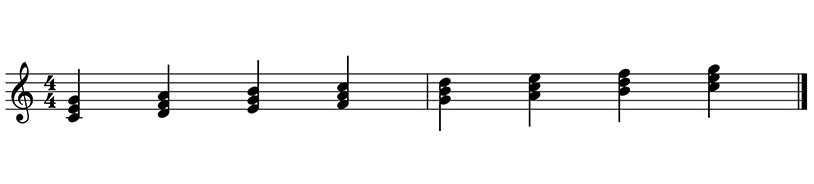

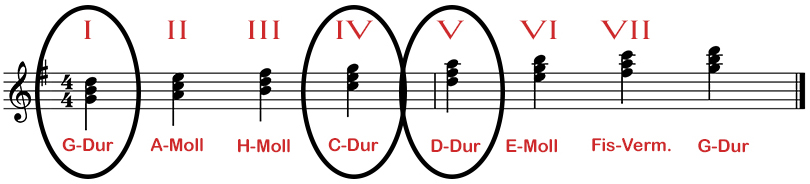

Let's take the I-IV-V cadence in G major again as an example. If we simply take the chords as in the example above, we get parallel directions of motion, and we don't want that.

If instead you vary the voicing so that not every voice goes in the same direction, you get the following notation:

The sound is so much more interesting, even though it is exactly the same chords. And that's just a very simple example - in more complex pieces with six-voice instruments, you can vary the voicing much more and make it more varied.

The function of a chord within a cadence

Each chord is assigned a degree, which in turn has a function within a song, determined by the key. As an example: If the key of the song is D major, then G major is step IV because G is the fourth note of the D major scale.

The following table shows the function of each degree in a major key:

| Level | Type | Designation |

|---|---|---|

| I | Major | Tonic |

| II | Minor | Subdominant parallel |

| III | Minor | Dominant parallel |

| IV | Major | Subdominant |

| V | Major | Dominant |

| VI | Minor | Tonic parallel |

| VII | Diminished | Diminished dominant seventh chord |

But when we are in a minor key, the chord types and some names change:

| Level | Type | Designation |

|---|---|---|

| I | Minor | Tonic |

| II | Diminished | |

| III | Major | Tonic parallel |

| IV | Minor | Subdominant |

| V | Minor | Dominant |

| VI | Major | Subdominant parallel |

| VII | Major | Dominant parallel |

As you can see, if you know the key and where the minor and major degrees are, you can very quickly find all the matching chords in a song - it's best to always use A minor or C major as a reference, because there are no accidentals.

Cadence as a principle of logic in harmony

Hugo Riemann was a German music theorist and musicologist who lived in the 19th and early 20th centuries. One of his main concerns was to better understand and explain musical structures and relationships. One of the central ideas in Riemann's theory was cadence as a principle of "musical logic".

Riemann understood the cadence as a kind of "musical grammar" that controls the flow of a musical composition and gives it a logical structure. He noted that harmony and the interplay of chords play a central role in the organization of musical pieces, a principle that is still very important to composition today.

By using cadences, a composer can control the tension and release within a piece and take the listener on a musical journey.

Hugo Riemann's principle of "musical logic" refers to the idea that music is based on a set of rules and structures that make it understandable and expressive. Cadences are a central aspect of this musical logic, as they control the movement and development of harmony within a piece and contribute to an orderly, meaningful structure as well as an appropriate conclusion.

Source: Riemann, Hugo - Musical Logic

Keep reading: Tritone - Here's what makes the devil's interval so special